A Space of Our Own

Happy living through co-housing

For someone trying to rent or buy an apartment in Hong Kong today, several questions jump immediately to mind. First, will I be able to afford it? Second, how much space will I have? And, finally, is it worth it?

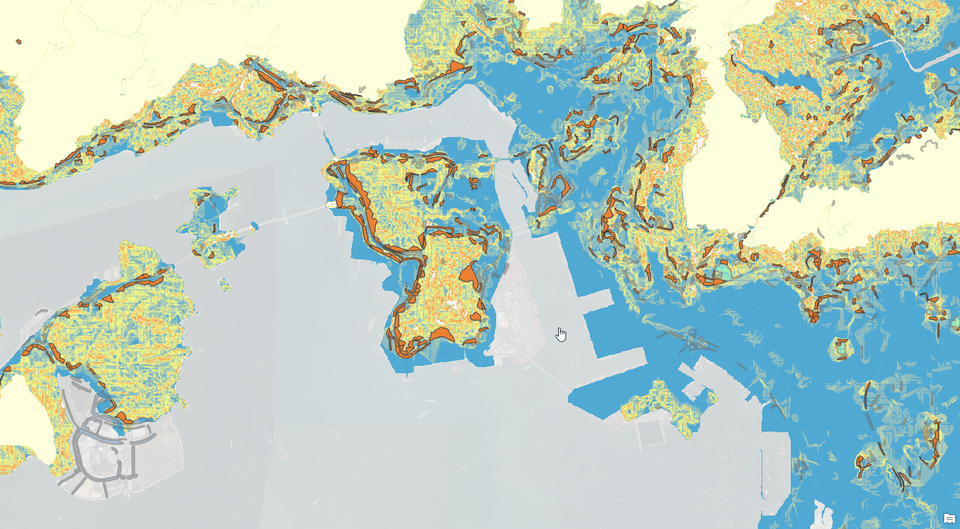

For a growing number of people, the first answer is an emphatic no (see “Where Space is Limited”). Time and time again (7 times, to be exact), Hong Kong’s housing market has been ranked “the world’s most unaffordable,” overtaking notoriously expensive cities such as Sydney and London, and prompting both criticism and social discontent, especially among the younger generations. But, even if one manages to afford a space of one’s own, its minuscule size will likely frustrate. In many new housing estates, the apartments fit little more than a bed and a desk, and are rendered affordable only by virtue of its smallness. Its worth, well… that depends.

Implicit in the concept of a so-called micro-unit is that size is directly proportional to cost; the smaller a space, the less expensive it is, and vice versa. In general, this does appear to hold true, but if one examines the recent trends in Hong Kong’s rental market, one finds that abnormalities abound (see fig. 1). Since 2014, the gap between the largest and smallest units have narrowed significantly, to the point that the smallest apartment has become more expensive than larger apartments.

This insight is valuable on its own, but an even more penetrating question can be asked: what if we can do away with this assumption altogether? what if, instead of accepting smallness as the only way out of big price tags, we change the way housing is organized so that size and comfort don’t have to be the necessary sacrifice in the temple of real estate?

One way this can happen is to reimagine the way we live. More and more, the phrase “sharing economy” is being heralded as the future of our economy, where resources are more efficiently shared among groups. Instead of each person owning a car, we now have car-share programs like Zipcar. In China, bike sharing services such as ofo have skyrocketed in popularity. Even the workspace can be shared now, thanks to companies like WeWork. What if this approach can be adapted to the way we live as well?

Since the mid-20th century, Denmark has been experimenting a version of this idea: co-housing. The premise is simple: instead of each family living in their own detached, suburban houses, multiple families would come together and build their homes together, with everything from the physical structure to household tasks such as cooking and child care taken care of collectively. The dream was to live purposefully together and create a stronger sense of community.

The first people to make this utopia-sounding dream a reality was 27 regular families in Denmark. They pooled their resources together and built individual homes connected by public spaces and common rooms–a configuration that helps preserve a reasonable degree of privacy while being conducive to collective activities. For example, instead of each family cooking and eating dinner and cleaning up afterwards on their own, the families would do this as a group, and in doing so, turn even the mundanities into a collaborative and social experience.

This idea soon caught on in other parts of northern Europe, such as the Netherlands and Germany, and, a decade later, in the United States, where more than 150 housing communities exist today. Far from being just a dream, co-housing is now a time-tested possibility for a growing number of people around the world.

While these co-housing communities were originally intended for the suburbs, however, its application is by no means limited to the suburbs alone; co-housing has equal promise for city dwellers as well. It has just adopted a different name: co-living.

Compared to co-housing, co-living is more nimble and compact. Instead of individual houses, it operates on the scale of apartments and buildings, where private and public spaces are divided by rooms. Often, though, the spaces come with a range of amenities to make the transition as seamless as possible. In New York, for example, where a significant portion of the population is transient, co-living holds particular appeal to those who wish to maintain an active social life despite their temporary residency.

More recently, a new co-living experiment has taken place in Taiwan. Known as 9-floor (玖樓), the project aims to spark new conception of a home . Tapping into small pockets of unused spaces, 9-floor redesigns and transforms them into cosy apartments shared somewhere between 3 or more people. But renovation is only the first step. The team behind 9-floor also invites and reviews resident applications to make sure that those who live there are invested in building a community together.

Since 1982, the average household size in Hong Kong has declined steadily. Meanwhile, the number of household has nearly doubled, dominated by 2– to 4-person families (see fig 2.). The percentage of single-person household has witnessed a slight increase, too. If we are concerned about maintaing what some sociologists have termed “social capital”, co-living may even be a promising solution to foster social interactions.

Once we can reimagine the home as a collective space, we may begin to pushback against the clasp between size and cost. Instead of trying to squeeze ourselves into ever smaller spaces, we can boldly steer in the opposite directions, and find community with like-minded people in a large and sociable space. The combination of solutions is ultimately limited if we only work within the strict parameters of size and cost. By including people in the picture, we can begin to see a new form of spaces that we can call ‘ours’.