Where Space Is Limited

Life unfolds regardless…

Say you want to buy an apartment in Hong Kong today, the going rate is around HK$11,200 (US$1,435) per square foot. To give this number some perspective, imagine you are a family of three looking for a 600-square-foot unit, the total cost comes out to be around HK$6.7 million (US$860,000). Assuming your family earns the city’s median household income of HK$28,000 per month, it will take you at least 20 years to pay for it, that is, if every dollar you make goes towards your 0%-interest-mortgage. 60 years is a far more realistic estimation considering costs for food, childcare, healthcare and well, mortgage interests. And how much is 600 square feet? About three standard parking spaces. In other words, 20 years of your labor earns you a parking space, which, as it turns out, is the average amount of space each person gets in Hong Kong. And if you live long enough, you might actually own that flat for you and your family before you die.

This astounding equation has rightly earned Hong Kong the title of the world’s least affordable housing, but the problem is far from being endemic. Albeit to lesser extents, housing affordability has become one of the most salient issues for many cities around the world. Driven by urban growth and fueled in part by market speculation, this phenomenon has escalated to a crisis status.

In order to tackle the affordability crisis, many cities governments are taking active measures to control prices and increase housing supply. In Hong Kong, where speculation plays a powerful role in pricing, the government started imposing higher duty stamps and other disincentives to deter investors. On the other hand, in London, where blame weighs more heavily on inadequate housing supply, Mayor Sadiq Khan has announced an ambitious plan to fund at least 90,000 new affordable homes over a six-year period. Even Facebook, a company with no obvious interest in real estate, has recently committed USD20 million to new home constructions in the Menlo Park-Palo Alto area where many of its tech workers live.

These measures will play an important role in curbing further price hikes, but they should not be seen as the only solutions. While market speculation has contributed to these rising figures, population growth remains the more salient issue. Writing on population in 1798, the British economist Thomas Malthus famously suggested that exponential population growth would eventually outpace agricultural output, resulting in widespread famine and population decline. Similarly, today’s urbanization may pose a similar challenge. Since the world became majority urban in 2008, the UN is all but certain that the urbanization trend will continue, with the total urban population exceeding six billion by 2045, nearly double that of 2008. Unless our housing supply can catch up with this rate, the housing crisis will almost certainly persist, or collapse in destructive ways

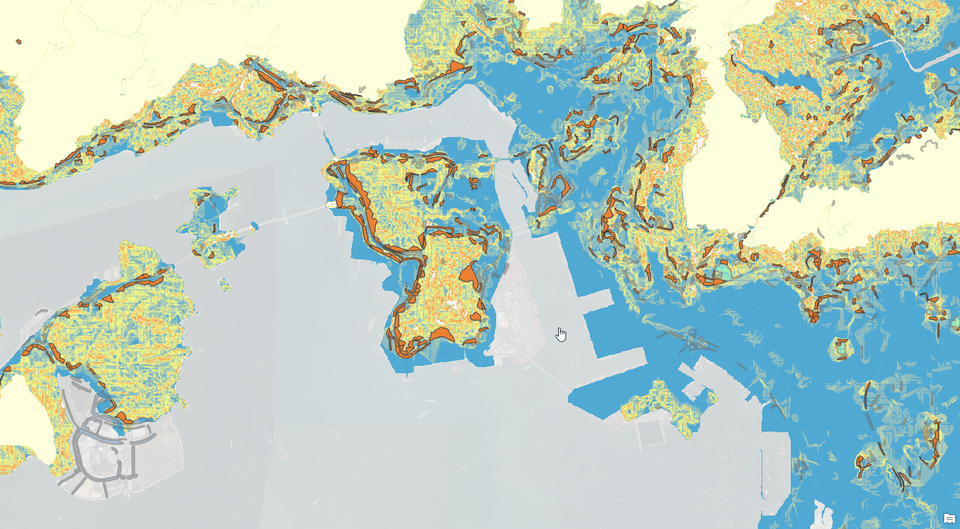

There are obvious reasons why cities will not be able to build as quickly. Even if all cities start building now, the fact remains that cities need land for new constructions. In many cases, a city is bound by its geography. San Francisco and Manhattan, for example, are confined to their respective peninsulas. In other cases, human restrictions like zoning and city boundaries are in place. Hong Kong, for example, designates about 40% of its land as country park where development is off limit to protect the natural habitat. More importantly, there exists a structural constraint that limits urban growth, namely, the economies of scale. Just as it can no longer be profitable for firms to expand production beyond a tipping point, a city can suffer losses from overgrowth. When a city grows too fast, it risks overburdening its infrastructure. The subway system, for example, becomes outnumbered by the passengers, and the commute becomes sluggish. The sewage and landfill will also reach capacity faster than expected, and creating tensions in waste management. All these factors have the potential to undermine a city’s governance.

From a planning perspective, too, over-urbanization can lead to broader consequences. People don’t just seek housing in a city; they also seek diversity of lifestyles. Whether it is a job or weekend entertainment, having options is key ensuring a satisfactory quality of life. These interests can at times diverge and translate into heated debates over land use. Should there be more green and public space? How are historic sites to be preserved? Where should new roads and transportation be built? All these questions are not purely cultural or environmental; they are also spatial. After all, there is only a limited amount of land available in any given location. A decision to privilege one use over another is bound to upset those who hold an opposing view. The future of our cities, therefore, will depend on how competing interests are resolved.

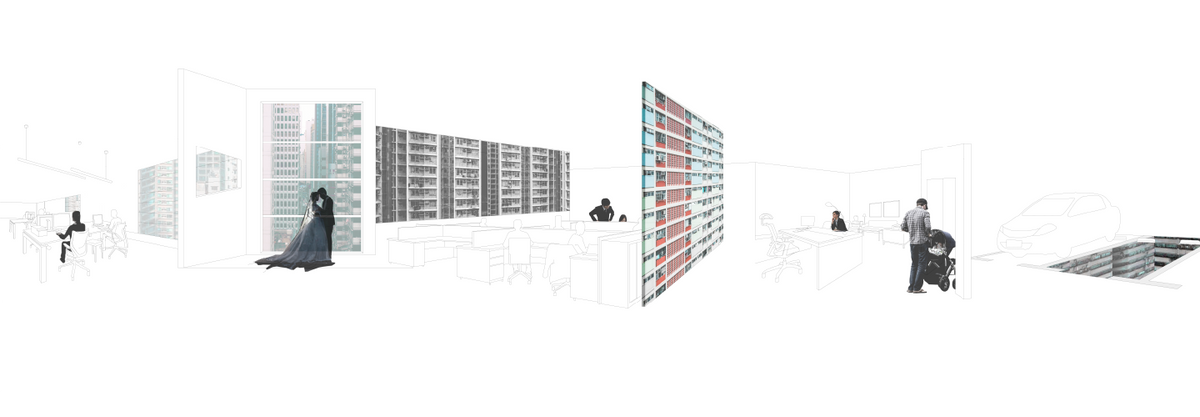

But for now, if we just limit ourselves to the problem of housing, one way to address this is to start thinking more creatively about how housing can be provided. Instead of just building new housing that require land a city doesn’t have, what if the city turns its attention to existing housing — the hardware — and ask if we can change our lifestyles — the software — to address this problem. To start, we can ask if the single-family home is still a compelling housing model? What if more household share common spaces and live closer together? Where one unit inefficiently accommodates one household in the past, now two households efficiently share the same public area, not unlike a dormitory or co-housing unit? Implementing these ideas will not be without challenges, but it also holds the potential to make our cities more efficient and social.